00. introduction

01. of man

02. of commonwealth

03. of a christian commonwealth

04. of the kingdom of darkness

download pdf

currently rough notes

before i start with this, i'll point out that my biases walking into it are pretty drastic. hobbes is really public enemy #1 to me. i can handle locke as being good intentioned but misguided - and realize that he's not really widely understood, either. hobbes, on the other hand, seems to be the source of the populist, "common sense" and largely intuitive opposition to leftist principles. "it's human nature!". that one drives me nuts...

i don't expect that the populist presentation of hobbes is going to be an accurate representation of the text. i expect a more subtle argument. yet, i don't expect to react any better. so, this is going to be a fairly nasty reaction to hobbes...

- i accidentally picked up an edited copy that removes hobbes' "theology" under the argument that he really didn't believe it anyways (but had to have a theological component in his political theory, or face religious and political persecution), so it's just a waste of time to bother with it. i've seen this argument before, applied most strikingly to newton, and i'm willing to take it seriously. however, i don't think it voids the theological sections of all value - it just means they need to be read critically. there may even be very revealing statements hidden in there. fear of god is central to hobbes' political ideology. so, i'm going to have to switch to an entirely different interpretation (i hesitate to use the word translation, but hobbes did not the speak the same language we do) halfway through to approach the theological parts. that being said, i am absolutely likely to gloss over most of it anyways....

- begins with some anachronistic statements about "materialism", which at the time was the idea that everything in the world can be modeled with mechanical motion - including humans. unless i can tie it to more modern conceptions of materialism, i'm going to skip over this, as it's not interesting to me.

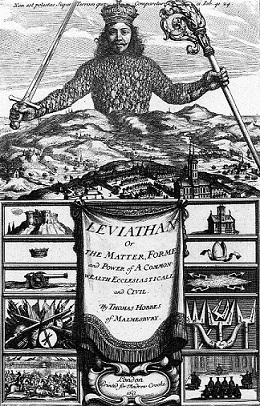

- in actuality, his conception of the state as a mechanical body in the opening pages of the text strikes me as being more connected to the idea of corporatism that developed out of the medieval guilds and culminated in 20th century fascism. hobbes is of course often accused of being the father of fascism, but i wasn't expecting anything that obvious quite that quickly.

- i'm also not going to spend any time with his baconian and anti-aristotlian and yet pre-newtonian concepts of physics, as they're not worth correcting - unless they're used in a political context. of senses presents somewhat of a false dichotomy of the topic (sensory organs interpret information bouncing off of outside objects); of imagination thankfully presents a gallilean understanding of newton's first law of motion, but isn't worth much without any concept of external force. the force of which hobbes states his ignorance is admittedly somewhat intriguing, but this is the extent of depth in response that the text really justifies when it comes to analyzing the physics of the mid seventeenth century.

- witches are justly punished for spreading superstitition. seems a little over the top. he also thinks the idea of fairies is being spread by the church to justify their own necessity. good conspiracy theory; probably a lot of truth to it.

- he further explains that schools ought to be rooting out superstitition by teaching materialism, but instead enforce it as a result of their ignorance. this is the second time he attacks the university in his first few pages, the first being that it teaches aristotlian (rather than gallilean) physics. while this is nice to see in the seventeenth century, his alternative ideas unfortunately leave a lot to be desired. the example he uses is of "imagination", which he explains as the motion of our senses fading - and it's unclear if he's thinking in aristotlean terms (the sense dying out) or if he thinks there's a force acting against our senses - rather than as creations of god or satan, depending on the moral character of the thoughts. rejecting the idea that we're controlled by god and/or satan may seem like a step out of the dark ages, but if the deity is to be replaced by a mysterious motion that cannot be altered then we haven't really done anything except change what our concept of god is from the perpetually meddling and heavily invested entity the defines the messianic religions into an aloof and disinterested deist one. he even goes so far as to reject the idea that imagination might arise spontaneously as a specious idea taught by the ignorant universities. worse, we're not using any kind of scientific method to arrive at this conclusion of deism, it's just stated authoritatively. this is not the way to reject religious thinking. i suppose i shouldn't be surprised, this is hobbes, but i don't want this commentary to reduce to an accusation of fallacy by authority, so i'm going to keep that to a minimum as well. certainly, hobbes is on the right track on some level, as all actions must on some level be reactions, but that's really *not* what he's trying to get across.

- take this point to the top: in topic after topic, hobbes presents a pre-modern understanding of things that is generally so primitive that it isn't worth responding to in a site like this. it may make more sense to come back to this page and record information as it relates to people that have corrected errors in hobbes. there are certain texts that have prevented human progress by promoting absolutely wrong ideas. is this one of them? hobbes may have been a genius of his time, but, read today, this text is just a lot of nonsense.

- concept of geometry is roughly kantian, and consequently every bit as wrong. wants philosophers to use the methods of geometers because their conclusions are "indisputable". this must have been influential on kant. but, roughly contemporary to kant, it was discovered (by gauss, bolyai, lobachevsky and others) that euclidean geometry is not the only possible geometry. and, the currently prevailing understanding of physics rejects euclidean geometry for hyperbolic geometry! so, what is so great about the method of geometers? the geometers themselves no longer use these methods. yet, strangely, the philosophers continue to.

- "while generally regarded as a text on political philosophy, leviathan is also a treatise on the natural sciences that was written before newton, einstein, freud, jung, darwin and gauss. further, while hobbes may have been friends with bacon, he shows no interest in the scientific method, preferring to emulate the synthetic philosophy of geometers past. worse, he builds his politics out of his understanding of the natural sciences using a method then referred to as materialism (which is related to but quite different than what we think of as materialism today). the result can only be described as a lot of nonsense, written from a point of extreme ignorance."

- from time to time, hobbes surprises but these surprises are a function of my own ignorance rather than hobbes' insight. the most important thing i've learned reading hobbes is that a number of ideas that i thought were attributable to newton are in fact older (and mostly attributable to galileo).

- hobbes was critical of classical scholarship, and it is good that he was. yet, hobbes himself is now classical, and his criticisms of aristotle now apply equally as well to himself.

- following the geometrical convention, first part is full of definitions. i'm not interested in this, because i know better. a modern geometer would leave essentially all of these as primitive terms. the value here is in understanding what hobbes means, not what the words themselves mean. he also goes through a long list of qualities, and merely states their value without argument. i don't see any value in analyzing any of this.

- religion is the result of not understanding cause and effect. quaint. unclear relevance.

- best to skip first part to deternine relevance for second. early ranking is an exaggeration...

- "men" are equal. from the equality arises competition, and of that diffidence and glory (although hobbes then isolates them as three causes of conflict, despite deriving the latter two from the first). it's all about ego. from there, he derives his idea that we're all in constant conflict (war) unless we have a state to keep us in order. compare to class conflict in marx.

- "it may seem strange to some man...that nature should thus dissociate, and render men apt to invade and destroy one another...but neither of us accuse man's nature in it." (143/144). he further denies that his state of nature ever existed, but suggests that neither morals nor property rights make any sense within it's abstraction. i use this argument repeatedly against ancaps, who somehow seem to think that markets can exist independently of government.

- right of nature - liberty of the individual to carry out it's self interest. and, liberty is merely a lack of external impediment (that is, 'negative liberty').

- first natural law: that every man, ought to endeavour peace, as far as he has hope of obtaining it; and when he cannot obtain it, that he may seek, and use, all helps, and advantages of war.

- second natural law: that a man be willing, when others are so too, as far-forth, as for peace, and defence of himself he shall think it necessary, to lay down this right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himself.

- note that hobbes is beginning from the old christian concept of "natural law" being ideas that are derived at through reason (although, like the modern secular humanists, he ignores the theological part). he acknolwedges the interconnection of law (obligation, responsibility) and right (freedom, liberty).

- his concept of rights is hard for me to intuitively understand, though. i mean, it's clear enough conceptually, but i can't grasp how anybody could be so ruthless as to actually believe it. he looks at the situation as though an individual renouncing bad behaviour is difficult to actualize because it means the same individual can't behave that way. so, if you consider the rule against plundering, for instance. none of us want to be plundered. but, he sees a conflict develop in people ("men") that would lead them to vote against anti-plundering laws under the argument that they wouldn't be allowed to plunder others. when you apply this sort of thinking to laws against murder, rape and other violent crimes, you get this horrific idea of "human nature" that seems hopelessly removed from the culture we live in. i've honestly never found myself conflicted this way, and couldn't imagine anybody else actually going through this thought process within our cultural surroundings. whether he was right at the time or not, hobbes very much comes off as archaic, anachronistic and out of touch when applied to life in this century.

- tries to understand injustice in terms of something illogical occurring. quaint.

- a contract is transferring a right from one individual to another. this is something rather different than classical liberal ideology. but, he states that certain rights (self-defense) cannot be transferred. he also thinks that contracts require violence to enforce, which i may agree with on a limited point. this is also an argument i use against ancaps.

- contracts require a consideration (gifts are not contracts). coercion is not a reason to void a contract (covenants entered into by fear are valid).

- presents a third law, that men perform their covenants made, but the usage of "law" is inconsistent. i mean, he then explains that such a law requires a threat of enforcement and blahblah. this is clearly a manmade law. might he have been trying to pull the cloak over? was he right in thinking the average reader was really that dumb? he then ties injustice to breaking the covenant, which is a crude sort of social contract. he also claims injustice is not defined unless there is the threat of enforcement of property rights, which makes my anarchist brain hurt.

- the association of natural law with self-interest produces the underlying implication that reason/logic are equivalent to self-interest. hobbes wants to create a situation where self-interest and group interest are the same thing, so produces the threat of consequence to keep people in line. at no point does he contemplate the idea of group interest being rational for it's own sake (and would have probably considered the idea as a kind of contradiction in terms). this makes his worldview deeply limited for contemporary application.

- he consequently argues against narrow self-interest by pointing out that it is not rational to incur the wrath of god or alienate possible friends. this is another argument i use against ancaps: free markets would necessarily collapse due to collusion, as self-interest is to co-operate. so, there's some childish linguistic word games regarding "justice" and "rational", but if a covenant only exists under threat of consequence, it is indeed obvious that it does not make sense to break the covenant (and endure the consequences).

- he does manage to consequently deduce the law in a way that's not really all that different than a modern darwinian conception of morality: we must hold to "covenants" for self-preservation. i still think it's inconsistent as a natural law, but it's not as bad as it first appeared.

- fourth law: a man which receiveth benefit from another of mere grace, endeavour that be which giveth it, have no reasonable cause to repent him of his good will. that is, people should be grateful. hobbes' reasoning is that people give to receive and also that they seek peace, but i'm not able to construct any kind of reason why this should be a law, especially given that gifts are not contractual. a better law would be that all gifts are trojan horses, and the lesson would be to avoid them.

- fifth law: complaisance, that every man strive to accomodate himself to the rest, which is just obviously false. this is a good example of the disconnect between logic and reality, and why logic is a poor tool to use to analyze humans with.

- sixth law: upon caution of the future time, a man ought to pardon the offences past of them that repenting, desire it. which is not english, but means that we must forgive for self-interest. that's again interesting for understanding modern ideas (dawkins' computer program video).

- seventh law: in revenges, men look not at the greatness of the evil past, but the greatness of the good to follow. again: clearly false, and indicative of the folly of interpreting humans as rational creatures.

- eighth law: no man by deed, word, countenance, or gesture, declare hatred, or contempt of another. lol. that;s a commandment, not a natural law...

- ninth law: every man acknowledge another for his equal by nature. his logic here is circular: because men are at war, they must think they are equal, otherwise they would not be at war. observation, not a law.

- tenth law: at the entrance into conditions of peace, no man require to reverse to himself any right, which he is not content should be reserved to every one of the rest.

- eleventh law: equity. if a man be trusted to judge between man and man, iy is a precept of the law of nature, that he be dealt equally between them.

- twelfth: such things as cannot be divided, be enjoyed in common, if it can be; and if the quantity of the thing permit, without stint; otherwise proportionably to the number of them that have right. distributive law, must conform to equity.

- thirteenth: the entire right; or else, making the use alternate, the first posessuib, be determined by lot. that is, first come first serve to things that cannot be split up evenly.

- fourteenth: all men that mediate peace be allowed safe conduct.

- fifteenth: that they that are at controversy submit their right to the judgment of an arbitrator.

- hobbes' golden rule: don't do things to others that you wouldn't want done to yourself.

- spirit of the law > letter of the law.

- again, these laws are deduced using logic (not really) and are consequently inalienable theorems of existence. that makes this moral philosophy a science (because hobbes thinks science is deductive) of the way things are.

- natural v artificial persons: person are actors, and they may act for themselves or for another. so, an artifical person would be something like a lawyer, or perhaps a slave. inanimate object may be represented but not impersonated. groups of people may be personated (does not use words like union or corporation), but the will is only binding on those who agree.

- part two....

- note: i may not agree that we're competitive by nature, but i do agree that the kind of self-interest that we must be conditioned with for capitalism to function necessitates the system hobbes is describing - that market anarchism is a utopian contradiction, in that it bases itself on self-interest that both only exists due to enforcement from above and requires regulation to prevent collusion and coruption. i'm consequently not reading hobbes so much as an argument for totalitarianism (and it seems to have nothing to do with communism at all) but as very explicitly against the ancap variety of liberal capitalism. when interpretated that way, which i think is correctly, i actually very strongly agree with him. it's really laughable to me to think that a system built on self-interest and enforced by contracts is in any way feasible in reality without a state standing around with a gun cocked at everybody's forehead. again, i would not respond by accepting authoritarianism, but by rejecting the idea of organizing society via markets.

- he's explaining his political construction in this section. we need a sovereign to keep us from eating each other, and to protect the community from enemies. that can be enforced from outside the community or arise from inside it. he talks in terms of the sovereign representing the will of everybody else, as though it is an artificial person. it's some kind of right-wing collectivism. almost an authoritarian marxism, with sovereign rather than proletariat....

- present hobbes as an authoritarian collectivist. strongly de-emphasize his so-called individualism (it's just not in the text, sorry). in describing the rights of the sovereign, hobbes is crystal clear. no other sovereign may be chosen. nobody can break free from the sovereign. there can be no dissent against the sovereign (and if any arises it may be treated as an act of war against the commmunity and stamped out with extreme violence). the sovereign only carries out the collective will of the people, and yet no person except the sovereign may be blamed for any transgression, as the collective and the sovereign are one. hobbes is describing the borg, not liberal ideology, and it does indeed all come from this idea of an artificial person as previously described, and of society as a working body (as described at the beginning - corporatism, fascism, materialism). hobbes completely rejects all individual thought in favour of conforming to the group will to be emancipated from the natural state of war of every man against every other. the sovereign speaks in one voice, and none may disobey. he also contrasts humans against bees in coming to this point, so it's a little ironic that he seems to be emulating a worker hive system.

- hobbes actually doesn't support private property in any kind of ideological sense. his sovereign would decide who should have what. as the sovereign is merely the will of the people, this is precisely the opposite of private property - it is public ownership of all goods. rather, he merely wants the division of property (or "use rights") to be clear so that people don't quarrel over it.

- commonwealth by institution may be monarchy, democracy or aristocracy. he explains that all three are authoritarian - which i'd also agree with, although i then conclude that all are illegitimate rather than that the one with the least resistance to the sovereign is preferable. he's not explicitly presenting an argument for monarchy yet, just pointing out some problems (as he sees them) in decentralizing power and questioning if the difference is ultimately an illusion (up to minimized efficiency with the illusion of decentralization). there is also the commonwealth by acquisition, which arises when actors band together to form a commonwealth out of fear of the sovereign rather than fear of each other. yet, the sovereign is still the representative of the commonwealth and cannot treat them differently (it must logically follow that there is only one commonwealth).

- hobbes presents a basic argument for reproductive rights that is something i've also argued for and have seen nowhere else. i'm not big into contract theory, but with the technology that exists today to facilitate birth control and abortion i find it difficult to sentence any male to fatherhood against his will. accidental pregnancy doesn't happen anymore, and can be terminated rather easily if it somehow does (i suppose due to ignorance) and the accident is fully unwanted. there consequently needs to be a sort of a trade off. women need to be in control of their own bodies, but the logical consequence of this is that men should not be held responsible for the child (aborted or not) unless they agree to enter into the arrangement. that reduces the process to two independent choices, rather than a unitary one - the would-be mother must first choose independently to have the child or not, and then the would-be father must choose whether to accept the responsibility of fatherhood. should he reject the responsibility, the would-be mother would of course be free to change her decision. hobbes is not as detailed, nor were abortion or birth control (safely) available in his time, but this is basically the argument he provides. it's one that modern law ought to take more seriously.

- he runs through what he sees as the rights and liberties of the subjects, working out various special cases. it's easily derived from the main points. nothing really interesting.

- likewise, he extrapolates his earlier posited conception of society as this "materialist" process of body parts working together mechanically to form a single body. he sees the parts as "body politics" and is clear that they cannot be above the law (and it follows from the earlier arguments that they could not disobey the sovereign). but it must also be that the sovereign obeys them, or it wouldn't be carrying out the will of the society. the various cases of who has authority over what are easily deduced from the provided principles and not worth exploring.